The Lady Ariel Side-Saddle Ordinary of 1874, shown above, is one of the most eccentric and innovative designs in the history of the bicycle as a gendered object.

The Ordinary, commonly known as the highwheeler or penny farthing, was first introduced in 1869 by French inventor Eugene Meyer. The design was popularised by James Starley, a leading English cycle manufacturer based in Coventry, in the 1870s. The Ariel was Starley’s signature model. The fact it was adopted as a model for a female rider was highly unusual for the time.

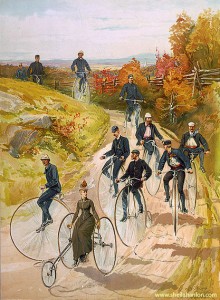

Highwheelers, including The Ariel, were produced with male cyclists in mind the 1870s and 80s. This was an age when highwheeling was popular as a sport and recreation among fit, young, men of means. These lofty machines were notoriously difficult to mount, propel, and control especially down hill. They were infamous for causing “headers.” Highwheelers were prohibitively expensive, making them accessible only to men of means who could afford their purchase price, upkeep and storage, and who had the time and space to ride them. A staunchly homosocial and competitive culture developed around highwheeling. The risk and physical demands of highwheeling, coupled with it’s association with masculine leisure pursuits, plus the incompatibility of the machine with long skirts precluded the involvement of women.

Highwheelers, including The Ariel, were produced with male cyclists in mind the 1870s and 80s. This was an age when highwheeling was popular as a sport and recreation among fit, young, men of means. These lofty machines were notoriously difficult to mount, propel, and control especially down hill. They were infamous for causing “headers.” Highwheelers were prohibitively expensive, making them accessible only to men of means who could afford their purchase price, upkeep and storage, and who had the time and space to ride them. A staunchly homosocial and competitive culture developed around highwheeling. The risk and physical demands of highwheeling, coupled with it’s association with masculine leisure pursuits, plus the incompatibility of the machine with long skirts precluded the involvement of women.

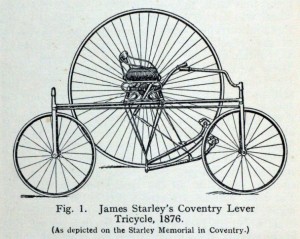

There was another machine deemed suitable for women in the 1870-80s–the tricycle. With its robust configuration, a bench seat rather than a saddle, and treadles instead of pedals the tricycle was considered safe, stable, and respectable enough for women of the aristocratic classes to ride. Some men not inclined to risk life and limb on a highwheeler also rode tricycles. The Starley Coventry Lever Tricycle of 1876 shown left, for example, was introduced in both men’s and ladies models.

There was another machine deemed suitable for women in the 1870-80s–the tricycle. With its robust configuration, a bench seat rather than a saddle, and treadles instead of pedals the tricycle was considered safe, stable, and respectable enough for women of the aristocratic classes to ride. Some men not inclined to risk life and limb on a highwheeler also rode tricycles. The Starley Coventry Lever Tricycle of 1876 shown left, for example, was introduced in both men’s and ladies models.

The Lady Ariel diverged from the familiar drop frame formula for adapting bicycles for women. A drop frame configuration, such as that seen in 1819 on London bicycle maker Denis Johnson’s Ladies Hobby Horse, was not feasible with the large front wheel of the highwheeler. The pattern of fixing a woman’s bench seat between the two large wheels of a tricycle put the rider much lower than their male highwheeling companions. This position proved hazardous when the machines toppled over and trapped riders as they were wanton to do.

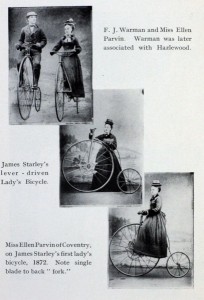

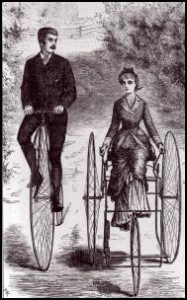

The Starley Company launched the highly experimental Lady Ariel in 1874. A prototype of the machine is captured in the image shown above, which appeared in Bartleet’s Bicycle Book, 1932. (A copy of the original image is held in The Science Museum Library and Archives). The picture shows Starley’s niece, Miss Ellen Parvin, posed on the ladies machine alongside Mr FJ Warman on the men’s model. It seems likely that the pair were posed for a promotional photo, and that the machine was a novelty rather than a machine intended for everyday use.

The Starley Company launched the highly experimental Lady Ariel in 1874. A prototype of the machine is captured in the image shown above, which appeared in Bartleet’s Bicycle Book, 1932. (A copy of the original image is held in The Science Museum Library and Archives). The picture shows Starley’s niece, Miss Ellen Parvin, posed on the ladies machine alongside Mr FJ Warman on the men’s model. It seems likely that the pair were posed for a promotional photo, and that the machine was a novelty rather than a machine intended for everyday use.

The photograph of the Lady Ariel indicates that it was a low mount highwheeler a few inches shorter than the standard version. Its front wheel was marginally smaller than the men’s model. Parvin sits on a broad seat fixed to the side of the frame and wheels and positioned towards the back wheel, not on a saddle over the machine like Warman is perched on. To make this arrangement possible, the frame of the machine was bent at two right angles, to create an off-set profile.

If you look carefully at the image, you will note that the front and back wheels of the Lady Ariel are not inline. Both treadles are affixed to one side of the wheel and the handle bars extend in the same direction. The principle behind the treadles is that the machine is propelled by moving the feet back and forth. This power is transformed into circuliar motion by the levers which then turn the hub-an overly complicated system to facilitate a leg motion considered a more lady like at the time. The front fork bends away from the front wheel to accommodate the treadle and rod propulsion gear. The main features that mark the Lady Ariel as a woman’s machine are the side-saddle configuration, broad seat instead of a saddle to eliminated the much tabooed straddling effect, treadles instead of peddles, and a shorter stature.

If you look carefully at the image, you will note that the front and back wheels of the Lady Ariel are not inline. Both treadles are affixed to one side of the wheel and the handle bars extend in the same direction. The principle behind the treadles is that the machine is propelled by moving the feet back and forth. This power is transformed into circuliar motion by the levers which then turn the hub-an overly complicated system to facilitate a leg motion considered a more lady like at the time. The front fork bends away from the front wheel to accommodate the treadle and rod propulsion gear. The main features that mark the Lady Ariel as a woman’s machine are the side-saddle configuration, broad seat instead of a saddle to eliminated the much tabooed straddling effect, treadles instead of peddles, and a shorter stature.

Positioning all the working parts of the machine and the rider on one side presented a challenge for balancing. Maintaining equilibrium would have been difficult, if not impossible. If the machine toppled over towards the hapless rider, she would be crushed under it’s weight. If it fell away from her, she would be virtually powerless to jump free and would be taken down with it, landing on top of the contraption. The highwheelers and tricycles of the 1870-80s were hefty machines with complex wheel spokes and sturdily constructed moving parts, making cyclists prone to injury when they were unfortunate enough to take a fall.

Miss Parvin’s riding costume characteristic of early cycling dress. The first tricycle dresses were modelled on the riding habits worn by aristocratic women for equestrian activities. They consisted of a long skirt and a matching tailored jacket constructed out of a heavy dark coloured fabric. The skirt has been designed in keeping with Victorian conventions that prescribed the concealment of the female form. The skirt is cut long to cover the rider’s full leg and feet while riding. If the rider was standing, her hem would have touched the ground. The knee is cut with additional fabric from a pattern that, if you imagine the skirt pulled out in front of the wearer, created an extra rectangle of material at knee level. This allowed extra room for the movement and bending of the leg, while obscuring any hint of motion or shapely legs. Another variation from Girls Own magazine shown right, uses a pleated underskirt to achieve a similar effect.

Miss Parvin’s riding costume characteristic of early cycling dress. The first tricycle dresses were modelled on the riding habits worn by aristocratic women for equestrian activities. They consisted of a long skirt and a matching tailored jacket constructed out of a heavy dark coloured fabric. The skirt has been designed in keeping with Victorian conventions that prescribed the concealment of the female form. The skirt is cut long to cover the rider’s full leg and feet while riding. If the rider was standing, her hem would have touched the ground. The knee is cut with additional fabric from a pattern that, if you imagine the skirt pulled out in front of the wearer, created an extra rectangle of material at knee level. This allowed extra room for the movement and bending of the leg, while obscuring any hint of motion or shapely legs. Another variation from Girls Own magazine shown right, uses a pleated underskirt to achieve a similar effect.

The Lady Ariel may not have been practical or commercially viable? but it is of interest to historians as an example of how bicycle innovators approached the challenge of designing a machine suitable for women within the gender limits of the late Victorian era.

Selected Sources

Bartleet, HW. Bartleet’s Bicycle Book, The Story of Cycles and Cycling. London: EJ Burrow and Co, 1931

Bijker, Weibe et al. The Social Construction of Technological Systems. Cambridge MASS: MIT Press, 1987.

Caunter, CF. The History and Development of the Bicycle. London: Her Majesty’s Stationary Office, 1956.

Ritchie, Andrew. King of The Road: An Illustrated History of Cycling. Berkeley: Ten Speed Press, 1975.

Woodforde, John. The Story of the Bicycle. London: Routledge, 1970.