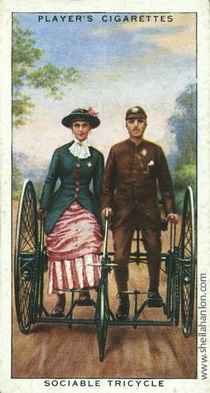

The wheelmen’s club, outfitted in dapper uniforms and racing en masse down a country road, is one of the enduring images of late Victorian masculine associational culture. Cycling clubs may have started out as male reserves, especially during the highwheeler age, but this status was challenged as more and more women took up the pastime in the 1890s. Most cycling clubs eventually made room for female members, though not without resistance. During the cycling craze, women’s cycling clubs such as the Lady Cyclists Association (LCA) shown above, flourished in Britain and other nations where cycling was a popular leisure fad.

Men’s Clubs, Mixed Clubs and the Growing Presence of Wheelwomen

Many of the earliest ladies cycling clubs were formed as a reaction to gender inequality in clubs run by men, but they quickly took on a character of their own. Victorian ladies cycling clubs encouraged women to ride, allowed them to take full part in club life, expanded the geography of women’s cycling through group rides, and insulated women from the hostility they faced in public as lone riders. The all-female cycling clubs of the 1890s were more than mere leisure associations–they were a space where women worked collectively to protect their rights as cyclists and citizens.

Many of the earliest ladies cycling clubs were formed as a reaction to gender inequality in clubs run by men, but they quickly took on a character of their own. Victorian ladies cycling clubs encouraged women to ride, allowed them to take full part in club life, expanded the geography of women’s cycling through group rides, and insulated women from the hostility they faced in public as lone riders. The all-female cycling clubs of the 1890s were more than mere leisure associations–they were a space where women worked collectively to protect their rights as cyclists and citizens.

Women had long been present on the margins of cycling club culture, even as far back as the 1870s when the machine of choice for men was the highwheeler. The tricycle, which was considered safe and appropriate for women riders, allowed lady tricyclists to join occasional rides as solo riders or on tandems and sociables. Most lady tricyclists were from aristocratic families who could afford the expensive machines, and they accompanied their husbands on club rides as guests.

ER Shipton, President of the Bicycle Touring Club (later the Cyclists’ Touring Club) noted that women on tricycles participated in club runs in the organisation’s early years, including 14 who attended an 1874 run. In 1880 the CTC set the precedent for admitting women as members when it enrolled Mrs WD Welford, wife of the club secretary, as their first female member. The Welfords are shown above riding a Salvo sociable on a John Player cigarette card issued in 1939 to commemorating 100 years of cycling history. Many other cycling clubs, especially those with a touring or social function, followed suit by extending membership to women in the 1890s.

The main impetus for extending membership to women was the increasingly mixed gender composition of the pastime following the introduction of the Safety bicycle. The decision to admit women, or not to admit them, often met with resistance from within club ranks. Clubs with a tradition of racing or road riding were most likely to reject the admission of women. In an 1891, for example, the captain of the Kilkenny Cycling Club threatened to resign if the club voted to admit women. (The club ruled in favour of women, and refused to accept his resignation letter.) An 1896 proposal to admit women to The Manchester Wheelers not only returned a resolute “No,” but led to the adoption of a clause in their constitution specifically barring women from joining. (We’re pleased to report that this still existent club now welcomes female riders.)

A Case for Women’s Cycling Clubs

By the 1890s, there were a number of ways for women to get involved in organised cycling. Some cycling clubs extended membership to women, though generally on limited terms. Another approach was to graft on a women’s auxiliary with its own officers, rides, and events. Finally, new clubs intended for both men and women were formed. These clubs often had a social, political, or class based agenda. The socialist leaning Clarion Cycling Club, shown here on an outing near Manchester, welcomed women from its start in 1894. Several elite clubs, such as The Wheel in London, provided opportunities for men and women to mingle in lavish club house and on extensive cycling grounds, insulated in this case by class exclusivity.

By the 1890s, there were a number of ways for women to get involved in organised cycling. Some cycling clubs extended membership to women, though generally on limited terms. Another approach was to graft on a women’s auxiliary with its own officers, rides, and events. Finally, new clubs intended for both men and women were formed. These clubs often had a social, political, or class based agenda. The socialist leaning Clarion Cycling Club, shown here on an outing near Manchester, welcomed women from its start in 1894. Several elite clubs, such as The Wheel in London, provided opportunities for men and women to mingle in lavish club house and on extensive cycling grounds, insulated in this case by class exclusivity.

None of these formulas for mixed cycling clubs proved ideal. Even the most seemingly egalitarian clubs were only marginally inclusive. Female members found themselves without equal voting rights, barred from all but a few rides, and excluded from central decision making. A reader complained in an 1899 letter to Queen, for example, that women did not feel wanted on CTC rides and events, suggesting that if women were represented on the board the club might serve them better. She would have to wait until 1907 to see a woman elected to a CTC office.

It soon became apparent that if women wanted to be represented and participate fully in cycling club life, they needed organisations of their own. In January 1890 a reader from Hammersmith, London wrote excitedly to Queen with news that a women’s only cycling club was in the works for her neighbourhood. “Several ladies belonging to clubs managed by men,” she explained, “have found that they are mere ciphers and their membership brings them no return in any way. they have therefore resolved to form a club of their own.” The club officially launched as the Ladies Cycling Club, making it one of the earliest all-female cycling organisations. Unfortunately, despite a strong start, the club quickly lost momentum–it didn’t survive the year.

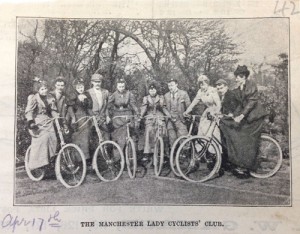

More ladies cycling clubs were soon to follow, especially during the bicycle craze years of 1895-98. According to the Englishwoman’s Yearbook for 1900 Edinburgh had at least four women’s cycling clubs, Dublin had two, and there was one in Wales. England had hundreds of local women’s cycling clubs including The Manchester Lady Cyclists est 1895 shown in the group photo above. Newcastle and Leeds both had prominent women’s cycling clubs, and Newcastle had four. Nottingham, Birmingham, Coventry, Oxford, Reading, Brighton and virtually every other town or region had at least one women’s cycling club by 1897.

More ladies cycling clubs were soon to follow, especially during the bicycle craze years of 1895-98. According to the Englishwoman’s Yearbook for 1900 Edinburgh had at least four women’s cycling clubs, Dublin had two, and there was one in Wales. England had hundreds of local women’s cycling clubs including The Manchester Lady Cyclists est 1895 shown in the group photo above. Newcastle and Leeds both had prominent women’s cycling clubs, and Newcastle had four. Nottingham, Birmingham, Coventry, Oxford, Reading, Brighton and virtually every other town or region had at least one women’s cycling club by 1897.

South and South West London were hot beds for women’s cycling organisations. Closely crowded together were the Ladies South West Bicycle Club est 1894, Brixton Ladies Cycling Club est 1896, Clapham Common Ladies Cycling Club est 1896, and the Clapham Park Lady Cyclists est 1897 just to name a few. The Kensington Ladies’ Cycling Club catered to wealthy residents of the upscale neighbourhood, while the Mowbray House Cycling Association was a co-op aspiring to class equality, and the Guy’s Hospital Nurses’ Cycling Association provided improving recreation for work-weary medical professionals.

A national organisation, The Lady Cyclists’ Association (LCA) was established in 1895. Its headquarters were at 35 Victoria Street in London, just down the road from the CTC. Its objective, according to founding member and President Lillias Campbell Davidson, was “to encourage and keep up the tone of cycling, to bring its members into touch with one another, to foster the wearing of the reform costume, and to find riding companions.” One of the LCA’s first initiatives was to produce a registry of approved inns and cyclists’ rests suitable for women on cycling rides or tours. This list paralleled the CTC’s well known system of endorsing cycling friendly establishments with winged wheel plaques. The LCA version took the needs of lady cyclists into consideration, such as steering clear of rural drinking spots frequented by local roughs with a reputation for showering women with unwanted attention and avoiding inn keepers who barred women in rationals.

Chief among the reasons cited for the appeal of women’s cycling clubs was relief from gender inequality in mixed clubs, short liesurely rides instead of long competitive ones, and a preference for female riding companions. The ‘safety in numbers’ principle offered protection from the insults and harassment solo lady cyclists commonly experienced. Ladies’ cycling clubs also offered an alternative to riding with a chaperone or male relative. In addition, women’s cycling clubs often had social and charitable functions. Most importantly, these were clubs run by women, for women.

Organisational Structure and Practice

Women’s cycling clubs were organised along similar lines to men’s cycling clubs. Most clubs were overseen by a council of officers including a president chosen for her social standing and dedication to cycling, a secretary or honorary secretary, a treasurer, and ride captains. Historian Patricia Vertinsky argues in her book The Eternally Wounded Woman that one of the LCA’s legacies was the fact that it “demonstrated that women were as good at working in associations as men.”

Women’s cycling clubs were organised along similar lines to men’s cycling clubs. Most clubs were overseen by a council of officers including a president chosen for her social standing and dedication to cycling, a secretary or honorary secretary, a treasurer, and ride captains. Historian Patricia Vertinsky argues in her book The Eternally Wounded Woman that one of the LCA’s legacies was the fact that it “demonstrated that women were as good at working in associations as men.”

Club programs revolved around weekly runs to scenic spots or respectable country inns on the outskirts of urban centres. The Ladies South West Bicycle Club based in Brixton visited Epsom, Richmond, Ripley, and Leatherhead. One of their longer trips was to Brighton and back. Regular meetings to discuss business, vet new membership, and plan events were an important part of the club calendar. In the winter off-season, most clubs suspended rides and offered dinners, dances, lectures, musical at homes, and evening entertainments.

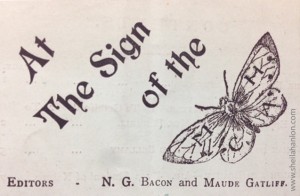

Uniforms, badges and colours were essential to club identity. The CTC’s winged wheel insignia and green tweed uniforms are among the more recognisable cycling regalia of the late nineteenth century. The Hammersmith Lady Cyclists Club settled on green and gold as their colours at their first meeting, the LCA chose a French inspired tri-colour for their badges and ribbons, and the MHCA adopted a butterfly emblem. (Shown right on the masthead of the MHCA newsletter.) For their uniform, most clubs selected a dark coloured skirt in a durable fabric, with a matching jacket, white blouse, hat, and embellishments in club colours. The Coventry Lady Cyclists Club wore a dark green skirt and jacket with panama hats trimmed in myrtle ribbon. Other clubs made the radical decision to adapt rational dress as their official uniform, such as the progressive MHCA and Lady Harberton’s Ladies Rational Dress Cycling Club.

Uniforms, badges and colours were essential to club identity. The CTC’s winged wheel insignia and green tweed uniforms are among the more recognisable cycling regalia of the late nineteenth century. The Hammersmith Lady Cyclists Club settled on green and gold as their colours at their first meeting, the LCA chose a French inspired tri-colour for their badges and ribbons, and the MHCA adopted a butterfly emblem. (Shown right on the masthead of the MHCA newsletter.) For their uniform, most clubs selected a dark coloured skirt in a durable fabric, with a matching jacket, white blouse, hat, and embellishments in club colours. The Coventry Lady Cyclists Club wore a dark green skirt and jacket with panama hats trimmed in myrtle ribbon. Other clubs made the radical decision to adapt rational dress as their official uniform, such as the progressive MHCA and Lady Harberton’s Ladies Rational Dress Cycling Club.

Leisure was central to ladies cycling clubs, but politics were never far behind. The political side of women’s cycling clubs began of course, with their endorsement of cycling for women which remained contentious in the 1890s. Rational dress was an unavoidable subject for women’s cycling associations, with clubs coming out both for and against it. In 1897, several clubs in favour of rational dress coordinated their efforts in a mass rational ride from London to Oxford for a meeting dubbed the “Congress of Rationals” by the press. About forty women and twenty men from The LCA, Ladies Rational Dress Cycling Club, Vegetarian Cycling Club, Ladies South West Bicycle Club, Yoroshi Wheel Club, and Western Rational Dress Cycling Club participated in the ride. The one rule of the event was that skirts would not be tolerated.

The political interests of women’s cycling clubs are apparent in the topics chosen for evening lectures and club newsletters. Dress reform, refugee rights, anti-vivisection, and of course suffrage were on the agenda. It was common for women’s cycling clubs to support causes through charitable drives, often for the benefit of needy members of their local community. The Clarion Cycling Club set the standard for charitable cycling drives with their well known Cinderella fetes, lantern rides, and parades in aid of poor children. The Clarion CC’s approach likely served as a model for women’s cycling clubs initiatives. The Leeds Ladies Cycling Club held a costume parade in aid of the New-Wortley Working People’s Hospital, while the Penzance Ladies’ Cycling Club focused fundraising efforts on soldiers’ widows and fatherless children.

The political interests of women’s cycling clubs are apparent in the topics chosen for evening lectures and club newsletters. Dress reform, refugee rights, anti-vivisection, and of course suffrage were on the agenda. It was common for women’s cycling clubs to support causes through charitable drives, often for the benefit of needy members of their local community. The Clarion Cycling Club set the standard for charitable cycling drives with their well known Cinderella fetes, lantern rides, and parades in aid of poor children. The Clarion CC’s approach likely served as a model for women’s cycling clubs initiatives. The Leeds Ladies Cycling Club held a costume parade in aid of the New-Wortley Working People’s Hospital, while the Penzance Ladies’ Cycling Club focused fundraising efforts on soldiers’ widows and fatherless children.

In the Edwardian era, women’s cycling took on an even more overtly political purpose as a suffrage campaign tool used for protests, publicity, practical purposes, and militant action–but that’s a blog topic for another time.

The Decline of Victorian Ladies Cycling Club and their Modern Revival

The vogue for women’s cycling clubs was to be a short lived. Few of the ladies’ cycling clubs established in the 1890s survived beyond the turn of the century. This downturn was not exclusive to women’s cycling clubs. Men’s and mixed clubs also folded or lost substantial numbers. Membership in the CTC, for example, plummeted from about 60,000 in 1899 to a mere 8,500 in 1918. Cycling clubs disbanded as the craze came to an end, the middle classes who made up the bulk of members moved on to new leisure fads such as motoring, and decreasing bicycle prices made the pastime more working class. This would later lead to working men’s and women’s cycling clubs for racing and recreation.

If we fast forward to today, women’s cycling is experiencing a renaissance. Women’s cycling advocacy initiative Breeze, for example, has established a network of women’s cycling groups across the UK. Local groups are flourishing, such as Manchester’s Team Glow which has over 100 members. Around the world, the all-women model is helping women get on the road for the first time in Yemen. Much like their Victorian predecessors, the benefits of modern all-women’s cycling club are said to include short leisurely rides, a non-competitive atmosphere, support from other women, and flexibility around work and family commitments.

If we fast forward to today, women’s cycling is experiencing a renaissance. Women’s cycling advocacy initiative Breeze, for example, has established a network of women’s cycling groups across the UK. Local groups are flourishing, such as Manchester’s Team Glow which has over 100 members. Around the world, the all-women model is helping women get on the road for the first time in Yemen. Much like their Victorian predecessors, the benefits of modern all-women’s cycling club are said to include short leisurely rides, a non-competitive atmosphere, support from other women, and flexibility around work and family commitments.

Perhaps our Victorian cycling sisters were on to a winning club formula.

Selected Sources

Primary

At The Sign of The Butterfly, 1895-9.

Papers of the Manchester Wheeler’s Club, Manchester Archive and Local Studies.

The Clarion, 1890-1900.

The Englishwoman’s Yearbook and Directory for 1900.

The Lady Cyclist, 1895-7.

The Pall Mall Gazette, 1890.

Queen, 1890-1900.

Wheelwoman, 1896-8.

Secondary

Hanlon, Sheila. “At the Sign of the Butterfly: The Mowbray House Cycling Association,” Cycle History, 18 (Spring 2008) 23-33.

Herlihy, David. Bicycle: The History. Yale University Press, 2004.

Norcliffe, Glen. Associations, “Modernity and the Insider-citizens of a Victorian Highwheel Bicycle Club,” Journal of Historical Geography Vol 19, Iss 2, (June 2006), pp 121-150.

Oakley, William. Winged Wheel: History of the First Hundred Years of the Cyclists’ Touring Club, Cyclists Touring Club, 1877.

Pye, Denis. Fellowship is Life: The Story of the Clarion Cycling Club. Clarion Publishing, 2004.

Vertinsky, Patricia. The Eternally Wounded Woman: Women, Doctors, and Exercise in the Late Nineteenth Century. University of Illinois Press, 1994.