Image: Leicester Mercury, 2017

The story of women’s suffrage is often presented as set in London and exclusively driven by middle and upper class women. Activists like Alice Hawkins, founder of the Leicester Women’s Suffrage and Political Union, however, were among the campaigners who brought the cause to all classes and all regions of Britain. Organising working class women in Northern or Midland towns and rural areas presented unique challenges, one of which was transportation. Alice Hawkins and her fellow suffragettes overcame this obstacle by jumping on their bicycles.

Alice’s Life and Political Awakening

Alice Hawkins was born into a working class family in Stafford in 1863. At age 13, she left school to take up work as a shoe machinist. Alice, to her good fortune, secured a position at the Equity cooperative boot and shoe factory. Employment on the shoe manufacturing floor introduced Alice to the struggles faced by the working classes and the important role of unions in securing workers’ rights. The inequalities faced by women in particular caught Alice’s attention and ire. Alice became active in the union movement, although she eventually grew disappointed in their limited scope, which prioritised the interests of male workers rather than equal rights.

Alice Hawkins was born into a working class family in Stafford in 1863. At age 13, she left school to take up work as a shoe machinist. Alice, to her good fortune, secured a position at the Equity cooperative boot and shoe factory. Employment on the shoe manufacturing floor introduced Alice to the struggles faced by the working classes and the important role of unions in securing workers’ rights. The inequalities faced by women in particular caught Alice’s attention and ire. Alice became active in the union movement, although she eventually grew disappointed in their limited scope, which prioritised the interests of male workers rather than equal rights.

The Midlands and North of England were fertile ground for women’s organisations concerned with the labour movement and the equal franchise. Alice joined the Independent Labour Party in 1892 and a Women’s Cooperative Guild was established at Equity in 1896. Alice’s politics left her wanting for something more; the early rumblings of the women’s suffrage movement caught her attention. By 1906, Alice was a member of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU).

In 1884, Alice had married Alfred Hawkins, a socialist who shared her political values. Alice and Alfred went on to have six children together. Alfred fully supported Alice’s commitment to the rights of women workers and later women’s suffrage. He was a founding member of the Men’s Political Union for Women’s Suffrage.

The Suffrage Movement Calls

In February 1907, Alice attended a WSPU meeting in Hyde Park, London. She heard the Pankursts speak for the first time, joining a packed crowd of like-minded women. Later that day, she participated in a mass march to the Houses of Commons to call for the vote for women. Alice was among the suffragettes arrested at the protest on charges of obstructing the police.

In February 1907, Alice attended a WSPU meeting in Hyde Park, London. She heard the Pankursts speak for the first time, joining a packed crowd of like-minded women. Later that day, she participated in a mass march to the Houses of Commons to call for the vote for women. Alice was among the suffragettes arrested at the protest on charges of obstructing the police.

Alice spent two weeks in Holloway Gaol with nearly thirty other WSPU detainees. On her release date, she and the other suffragettes were met at the gate by a crowd of supporters and a music band. After this baptism by fire, Alice was hooked on the WSPU and all it stood for.

The Leicester Women’s Social and Political Union

Keen to start a WSPU branch in Leicester, Alice invited well known suffragette Sylvia Pankhurst to speak as a catalyst to spark interest. It worked, and the Leicester WSPU was officially established.

Keen to start a WSPU branch in Leicester, Alice invited well known suffragette Sylvia Pankhurst to speak as a catalyst to spark interest. It worked, and the Leicester WSPU was officially established.

Sylvia Pankhurst formed an enduring relationship with Alice and the women of Leicester. She later returned to Leicester to explore working class women’s lives including the experiences of Alice’s co-workers at the Equity factory and to help organise meetings of the Leicester WSPU branch. She drew and photographed many of the women she met at Equity, including Alice who is believed to be the subject of a watercolour painting now held at the Leicester Museum.

By 1908, Alice had made a name for herself as a committed WSPU organiser, speaker and protester. She joined the likes of the Pankhursts on the hustings at the 1908 WSPU Hyde Park meet, addressing an estimated 250,000 people.

By 1908, Alice had made a name for herself as a committed WSPU organiser, speaker and protester. She joined the likes of the Pankhursts on the hustings at the 1908 WSPU Hyde Park meet, addressing an estimated 250,000 people.

Alice was among the women who made a point of not being home to be registered during the Census Boycott on 2 April 1911. Votes for Women, 24 March 1911 reports that the Leicester WSPU organised an all night party at their 14 Bowling Green headquarters for women to stow away, arguing “No vote, no census.” In Vanishing for the Vote, Jill Liddington provides documentation that about 20 women ranging in age from 17-50 were seen loitering as part of the “mass evasion.”

Over the course of her career as a WSPU militant, Alice was arrested and incarcerated five times. One of her arrests was linked to then Home Secretary Winston Churchill’s 1909 visit to Leicester. When Alice was barred from The Palace Theatre where Churchill was due to speak, her husband Alfred stood in for her to demand the vote for women. Alfred was swiftly ejected from the meeting. Alice, Alfred and several other suffragettes attempted to re-gain entry and were arrested. Alice found herself in Leicester Gaol where she and Mary Watts went on hunger strike. She was also arrested on Black Friday in November 1910, November 1911 for breaking the window of the Home Office and in 1913 for attacking a pillar box in Leicester.

Suffragette Cyclists

The Leicester WSPU’s first priority was to recruit supporters. They did so through open air talks in village squares, greeting women at factory gates and visits to the surrounding towns and countryside. This is where the bicycle came in handy.

Alice likely learned to ride in the late 1890s. As a working class lass, bicycles would have been prohibitively expensive during the early craze years of the mid 1890s. Alice was a member of the Clarion Cycling Club, a socialist recreational group connected with Robert Blatchford’s Clarion Newspaper. Many other future suffragettes, including the Pankhursts, also joined their local Clarion Cycling Clubs. A 1902 newspaper report claimed that as a member of the Clarion Cycling Club, Alice was accused of “outraging public decency” by riding in rational dress.

Alice and her fellow suffragettes used their bicycles as transportation around Leicester and to travel to the nearby countryside and neighbouring towns. In 1909, Alice, with the support of Gladice Keevil of the Birmingham WSPU, spearheaded a bicycle drive to increase membership in the Leicester WSPU by targeting supporters beyond city limits. It was so successful that enough new members were recruited to establish a new WSPU satellite branch in Loughborough. In the summer of 1910, Hawkins and others suffragettes set out every Sunday morning to rural villages including Syston, Shepshed, Castle Donington, Kibworth, and Melton Mowbray, ranging from 6 to 30 miles away. Once they arrived at their destination, they held open air meetings, greeted supporters, distributed WSPU literature and solicited donations.

In his biography of Alice, Alice Hawkins and the Suffragette Movement in Edwardian Leicester. Richard Whitmore writes that during the 1911 general election the Leicester WSPU cyclists dressed in suffragette colours and rode over to the Loughborough “Votes for Women” shop to distribute anti-Liberal pamphlets. WSPU member Bertha Clark remembered the ride fondly, noting as Whitmore reports, “approaching Loughborough, my badge and the union colours of green, white and purple drew salutes from smiling strangers.”

The bicycle played a small but vital role in the Leicester WSPU’s fight for the women’s suffrage.

Hometown Hero

Despite her central place in the national WSPU, Leicester remained close to Alice’s heart and her campaigning always included her home town. With the outbreak of World War I in 1914, Alice continued to call for women’s suffrage. This was a departure from the WSPU’s central decision taken by Christabel and Emmeline Pankhurst to suspend campaign work in support the war effort. The Representation of the People Act of 1918 enfranchised women over the age of 30 who met the property qualification. Although only 40% of women in Britain met the criteria to vote, it was a step in the right direction and a sign of greater enfranchisement to come. In 1928, all women would get the vote on equal terms as men.

Despite her central place in the national WSPU, Leicester remained close to Alice’s heart and her campaigning always included her home town. With the outbreak of World War I in 1914, Alice continued to call for women’s suffrage. This was a departure from the WSPU’s central decision taken by Christabel and Emmeline Pankhurst to suspend campaign work in support the war effort. The Representation of the People Act of 1918 enfranchised women over the age of 30 who met the property qualification. Although only 40% of women in Britain met the criteria to vote, it was a step in the right direction and a sign of greater enfranchisement to come. In 1928, all women would get the vote on equal terms as men.

Alice’s prominence in trade unionism, the labour movement and women’s suffrage was remembered in her obituary when she died in 1946. In 1992, a blue plaque was erected on the Equity Shoe factory marking Alice’s contribution to history.

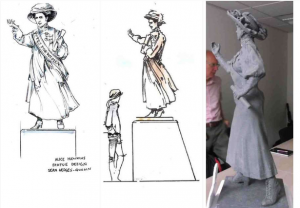

In more recent years, a grass roots campaign initiated by Alice’s great-grandson Peter Barratt successfully petitioned for a statue erected in Alice Hawkin’s honour. The memorial will be erected in 2018 to coincide with the centennial of the Representation of the People Act. Designed by sculptor Sean Hedges-Quinn, it depicts Alice as she may have looked in 1912 at the height of her WSPU activism.

Alice’s legacy has also inspired women to cycle. In 2011, Cycles and Suffragettes formed as an initiative to encourage women to cycle in Leicester. As part of the 2017 Leicester Inside Out Festival, the Laurielorry Theatre Company presented “Alice in her Shoes,” a suffrage protest reenactment and street performance based on Alice’s campaign for the vote.

Alice’s legacy has also inspired women to cycle. In 2011, Cycles and Suffragettes formed as an initiative to encourage women to cycle in Leicester. As part of the 2017 Leicester Inside Out Festival, the Laurielorry Theatre Company presented “Alice in her Shoes,” a suffrage protest reenactment and street performance based on Alice’s campaign for the vote.

Further Information About Alice

For further information about Alice Hawkins, visit www.alicesuffragette,co.uk. Peter Barratt has created an excellent website dedicated to his great-grandmother Alice’s life and legacy. The site tells Alice’s story in detail and is beautifully illustrated with artefacts and memorabilia from her personal collection.

You can watch several videos on the site about Alice’s campaign for women’s rights and enfranchisement.

Selected Sources

“Alice Hawkins,” The Women’s Suffrage Who’s Who, 1913

Ackers, Peter. “Experiments in industrial democracy: an historical assessment of the Leicestershire boot and shoe co-operative co-partnership movement” Labour History, Volume 57, Issue 4, 2016

Barratt, Peter. “Alice Hawkins Suffragette – A Sister of Freedom,” www.alicesuffragette.co.uk

Crawford, Elizabeth. “Alice Hawkins” The Women’s Suffrage Movement: A Reference Guide, p 281.

Dawson, Louise. “How the bicycle became a symbol of female emancipation,” The Guardian, 4 November 2011

Liddington, Jill “Vanishing for the Vote: Suffrage, citizenship and the battle for the census,” Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2014.

“Statue success for Leicester Suffragette Alice Hawkins,” BBC News, 17 October 2015

Whitmore, Richard. Alice Hawkins and the Suffragette Movement in Edwardian Leicester. Derby: Breedon Books Publishing Co Ltd, 2007.