The Sylvia Pankhurst Memorial Lecture 2018 took place at Wortley Hall, near Sheffield before a packed audience. The topic was “Pedalling Days: Sylvia Pankhurst and Political Cycling Traditions from Clarionettes to Suffragettes.” Previous speakers have included Dr Helen Pankhurst and Dr Richard Pankhurst.

As an exciting addition to the lecture, Pedal4Pankhurst organised sponsored rides to fundraise for the statue of Sylvia that will soon be erected in Clerkenwell Green. You can support the Sylvia Statue by visiting the Just Giving fundraising page.

Curious about Sylvia’s cycling connections? You can read an abbreviated summary of the talk below.

“Pedalling Days: Sylvia Pankhurst and Political Cycling Traditions from Clarionettes to Suffragettes”

Dr Sheila Hanlon, August 2018

With the Sylvia Pankhurst Memorial statue campaign in full swing and the centennial of the 1918 Representation of the People Act being celebrated, it is an honour to be addressing cycling and suffrage as the 2018 Sylvia Pankhurst Memorial Lecturer.

With the Sylvia Pankhurst Memorial statue campaign in full swing and the centennial of the 1918 Representation of the People Act being celebrated, it is an honour to be addressing cycling and suffrage as the 2018 Sylvia Pankhurst Memorial Lecturer.

Sylvia Pankhurst’s important legacy as a leading suffrage and human rights campaigner is beginning to get the recognition it deserves. Much less is known about her participation in another progressive activity with a political edge; cycling.

Sylvia’s cycling world included rides with her family, the politics of the Clarion Cycling Club and campaigning for the vote with the cycling suffragettes. Cycling and suffrage intersected in Sylvia’s personal and political life.

Who was Sylvia?

Estelle Sylvia Pankhurst was born 5 May 1882 on Drayton Terrace, Old Trafford Manchester. She was one of five children born into the highly politicised family of Richard and Emmeline Pankhurst. Christabel was the oldest born in 1880, followed by Sylvia, then Adela born 1885, then Richard and Henry. The Pankhurst children grew up in a politicised family alongside the Labour, socialist and suffrage movements. Sylvia’s father Richard, was lawyer and prominent member of the Independent Labour Party; her mother Emmeline was a giant among suffrage figures as well as a shop keeper and civil servant. Both supported the women’s franchise. Education was also important to them. Sylvia studied at Manchester High School for Girls, Manchester School of Art and the Royal College of Art in South Kensington.

Estelle Sylvia Pankhurst was born 5 May 1882 on Drayton Terrace, Old Trafford Manchester. She was one of five children born into the highly politicised family of Richard and Emmeline Pankhurst. Christabel was the oldest born in 1880, followed by Sylvia, then Adela born 1885, then Richard and Henry. The Pankhurst children grew up in a politicised family alongside the Labour, socialist and suffrage movements. Sylvia’s father Richard, was lawyer and prominent member of the Independent Labour Party; her mother Emmeline was a giant among suffrage figures as well as a shop keeper and civil servant. Both supported the women’s franchise. Education was also important to them. Sylvia studied at Manchester High School for Girls, Manchester School of Art and the Royal College of Art in South Kensington.

In 1903, Emmeline founded the Women’s Suffrage and Political Union (WSPU) at a meeting held in the family home, 62 Nelson Street Manchester. (Now The Pankhurst Centre.) Emmeline and Christabel rose to prominence as leaders of the movement, but Sylvia also contributed in her own way. In addition to regular campaign work, Sylvia was appointed full time organiser for the London branch of the WSPU in 1906, used her artistic skills to design WSPU emblems and pageantry and recorded the history of the movement. In contrast to her mother and sister, Sylvia maintained an interest in socialist and working class politics, bolstered in part by her close friendship with trade unionist and labour leader Keir Hardie. In 1907-8, Sylvia embarked on a tour of industrial towns to document and paint the working lives of female industrial labourers. One of her stops was Leicester where she studied shoemakers and met and befriended Alice Hawkins, another prominent cycling suffragette.

By 1912, it was clear that Sylvia’s path had diverged from that of Emmeline and Christabel. WSPU violence did not sit well with her, Emmeline and Christabel positioned themselves as autocratic leaders, and competing figures such as Pethick-Lawrences were ousted from the group. Sylvia was left on one side of an irreparable family rift. Sylvia reacted by applying her brand of socialism, labour and suffrage to the East End, forming a new democratic organisation: the East London Federation of Suffragettes (ELFS). It a headquarter on Old Ford Road, Bow magazine The Dreadnought, and a people’s army of men and women ready for action. Arrests followed—eight between 1913 & 1914 alone—but so too did personal satisfaction that she was making a difference.

By 1912, it was clear that Sylvia’s path had diverged from that of Emmeline and Christabel. WSPU violence did not sit well with her, Emmeline and Christabel positioned themselves as autocratic leaders, and competing figures such as Pethick-Lawrences were ousted from the group. Sylvia was left on one side of an irreparable family rift. Sylvia reacted by applying her brand of socialism, labour and suffrage to the East End, forming a new democratic organisation: the East London Federation of Suffragettes (ELFS). It a headquarter on Old Ford Road, Bow magazine The Dreadnought, and a people’s army of men and women ready for action. Arrests followed—eight between 1913 & 1914 alone—but so too did personal satisfaction that she was making a difference.

During WWI, Emmeline and Christabel suspended their suffrage campaign and redirected the WSPU’s energy into the war effort. Sylvia disagreed with to this approach and carried on the fight for women’s suffrage with the ELFS, later rebranded as the Workers’ Socialist Federation. After the vote was won, Sylvia continued to campaign for people’s rights. She briefly supported a branch of the Communist Party, but it was a poor fit. In 1927 at age 45, Christabel had a son Richard with Italian artist and anarchist Silvio Corio. In the 1930s, she took up the political causes of Ethiopia, befriending Haile Selassie. In 1956, she moved to Addis Ababa with Richard, where she died 27 Sept 1960.

Sylvia the Clarion Cyclist

Cycling, like suffrage, was a family affair for the Pankhursts. Christabel was the greatest cycling enthusiast of the lot, with Sylvia a close second. According to Adela’s biographer Verna Coleman, however, the youngest Pankhurst sister was not fond of the pastime.

Cycling, like suffrage, was a family affair for the Pankhursts. Christabel was the greatest cycling enthusiast of the lot, with Sylvia a close second. According to Adela’s biographer Verna Coleman, however, the youngest Pankhurst sister was not fond of the pastime.

The Pankhurst family joined the Clarion Cycling Club (CCC) in 1896. The CCC, formed in 1894 in Birmingham, was a socialist cycling group associated with Robert Blatchford’s radical newspaper The Clarion. The CCC combined political activism with recreational cycling. Bands of Clarion Scouts served as socialist missionaries, holding meetings in rural villages, distributing pamphlets, leaving behind copies of the Clarion, selling Blatchford’s Merry England, and drumming up support for the cause. Sylvia noted in The Clarion that, “the Clarion people carried a leaven of Socialist conversation and argument into rural districts then wholly untouched by any Socialist or Labour propaganda.”

Unlike many other 19th Century cycling organisations, the CCC welcomed working class  cyclists. Even more unusually it extended membership to women. Early invites to club meets often noted that ladies were especially welcome, and generally a handful did attend. The CCC was not, however, wholly egalitarian. Women remained a minority among members, and gender roles and gentle sexism persisted. An 1895 report from the Manchester CCC noted, “Lady members add a great amount of interest to our clubs runs and are a real source of help to us, mere men, when it comes to the inevitable tea-time.” Perhaps even more off-putting for the Pankhursts would have been The Clarion’s official line on suffrage. Leader Robert Blatchford refused to back women’s enfranchisement, in part because he feared it would weaken the case for working class men’s rights.

cyclists. Even more unusually it extended membership to women. Early invites to club meets often noted that ladies were especially welcome, and generally a handful did attend. The CCC was not, however, wholly egalitarian. Women remained a minority among members, and gender roles and gentle sexism persisted. An 1895 report from the Manchester CCC noted, “Lady members add a great amount of interest to our clubs runs and are a real source of help to us, mere men, when it comes to the inevitable tea-time.” Perhaps even more off-putting for the Pankhursts would have been The Clarion’s official line on suffrage. Leader Robert Blatchford refused to back women’s enfranchisement, in part because he feared it would weaken the case for working class men’s rights.

In a 1931 article for The Clarion called “Pedalling Days,” Sylvia recalled joining the CCC at age fourteen in 1896. Fellow club member Mrs Bennett taught her to ride, and although Sylvia had some trouble learning at first including a collision with a pony cart, she eventually got the hang of it. “For the next two years,” she explained “we rode with the club every Sunday.”

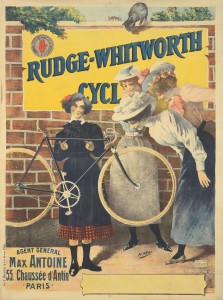

Sylvia recorded another side of her cycling experiences in her 1931 memoir The Suffragette Movement—the trials and tribulations of riding with Christabel. When Christabel decided to take up cycling, she was drafted in as her chaperon. Christabel invested in a good quality Rudge Whitworth bicycle priced at £30. Sylvia, in contrast –worried about family finances—opted for a cheap home-made model improvised from gas piping. Christabel was the superior cyclist, often leaving Sylvia in her dust. Sylvia recalled, “It was when riding alone with Christabel that I endured a veritable torture. My crimson face and gasping breath were the wordless answer to her impatient ‘Come on!’ Afraid of being considered a nuisance, I would strain and strive till it seemed that my heart would burst. Finally she would disappear from me, climbing some hill, and arrive home somehow an hour before me.”

Sylvia recorded another side of her cycling experiences in her 1931 memoir The Suffragette Movement—the trials and tribulations of riding with Christabel. When Christabel decided to take up cycling, she was drafted in as her chaperon. Christabel invested in a good quality Rudge Whitworth bicycle priced at £30. Sylvia, in contrast –worried about family finances—opted for a cheap home-made model improvised from gas piping. Christabel was the superior cyclist, often leaving Sylvia in her dust. Sylvia recalled, “It was when riding alone with Christabel that I endured a veritable torture. My crimson face and gasping breath were the wordless answer to her impatient ‘Come on!’ Afraid of being considered a nuisance, I would strain and strive till it seemed that my heart would burst. Finally she would disappear from me, climbing some hill, and arrive home somehow an hour before me.”

The Pankhurst family took part in regular cycling outings with the Clarion Cycling Club and supporting their political and charitable work. An 1896 letter to the Clarion Cyclists Journal noted that Dr. Pankhurst and his family visited a Cinderella camp held by the club to provide holidays for deprived children. Special thanks went to Mrs Pankhurst for a donation of clothing. They Pankhursts also attended annual CCC summer camps. These camps were a highlight of the Clarion calendar, and took place in bucolic rural spots. In 1895, The Clarion‘s “Cycling Notes” correspondent Swiftsure reported that the annual camp at Pickmere, Cheshire consisted of a van, marque, and three bell tents one of which was reserved for ladies and children. The Pankhursts opted to stay nearby, rather than lodge with the masses who had a reputation for rowdiness.

The Clarion Cycling Club was an important part of the Pankhurst’s family life. The girls grew up reading The Clarion, and met key figure in the socialist movement, such as Blatchford, in their family home. When Richard Pankhurst died in 1898, a band of Clarion Cyclists rallied together to accompanied his funeral procession. The death of her father marked the end of Sylvia’s carefree days of youth. She gave up her membership in the Clarion CC, explaining “my life had become far too serious and too anxious to leave room for cycling.”

Cycling to Suffrage

Cycling played an important role in another side of Sylvia’s life – the women’s suffrage movement.

Cycling played an important role in another side of Sylvia’s life – the women’s suffrage movement.

Bicycles have long been connected to women’s emancipation. Women were there on the margins as far back as 200 years ago when the first proto-bicycle was invented, the draisienne. While only a few women took to the high wheelers of the 1870s, mostly professional racers, the invention of the safety bicycle in the 1880s transformed cycling into a popular form of mass leisure. During the 1890s cycling craze, women accounted for a third of bicycle riders, most of whom were middle and upper class. Ladies drop frames were available in virtually all makes, women’s cycling magazines flourished, and lady cyclists rode everywhere from private academies and quiet park lanes to public thoroughfares and country lanes.

The association of cycling with new women was quickly established. The pastime caused great moral and medical debate ranging from the physical dangers of riding to the social consequences of women’s mobility. Gendered social anxieties led to fears that women would cycle away from the domestic sphere, abandon their husbands and children, become manly, and evade their chaperones. Cycling dress was a contentious issue. Rational knickerbocker cycling costumes were the most practical outfit but their association with masculinity and the negative reception they received in public led most women to stick to long skirts.

great moral and medical debate ranging from the physical dangers of riding to the social consequences of women’s mobility. Gendered social anxieties led to fears that women would cycle away from the domestic sphere, abandon their husbands and children, become manly, and evade their chaperones. Cycling dress was a contentious issue. Rational knickerbocker cycling costumes were the most practical outfit but their association with masculinity and the negative reception they received in public led most women to stick to long skirts.

Sylvia was among the early adopters of cycling. So to were many other progressive women whose names you will recognise from the Edwardian suffrage movement: Millicent Garrett Fawcett (NUWSS leader), Emily Wilding Davison (suffragette martyr), Sarah Grand (feminist author) and others. It is not surprising that the lady cyclists of the 1890s later turned their bicycles to politics.

At the dawn of the 20th century when the women’s suffrage movement gained momentum, campaigners marshalled every resource available into the battle for the vote. Bicycles were among the tools at hand. Bicycles were integrated into the suffrage campaign in ingenious ways, ranging from peaceful protests to militant missions. There was even a “Votes for Women” bicycle produces by the Elswick company and painted in the WSPU colours, purple white and green. It was embellished with a medallion of freedom, based of course on Sylvia’s design.

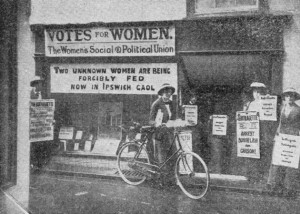

Cycling suffragettes and suffragists were particularly helpful for promoting events. One well-known image shows two suffragettes with bicycles advertising a talk by Mrs Pankhurst. To advertise the WSPU’s 1908 Hyde Park Demonstration, Jus Suffragii reported “parties of cyclists…[rode] through the streets with decorated machines, distributing leaflets and holding short meetings.” The “Holiday Campaign” encouraged women to continue their work for the cause during the summer season, and often saw suffragette cyclists advertising meetings in seaside resorts. Orderly brigades of Suffragette Scouts operated much like the Clarion Scouts to take the suffrage message to outlying areas.

Cycling suffragettes and suffragists were particularly helpful for promoting events. One well-known image shows two suffragettes with bicycles advertising a talk by Mrs Pankhurst. To advertise the WSPU’s 1908 Hyde Park Demonstration, Jus Suffragii reported “parties of cyclists…[rode] through the streets with decorated machines, distributing leaflets and holding short meetings.” The “Holiday Campaign” encouraged women to continue their work for the cause during the summer season, and often saw suffragette cyclists advertising meetings in seaside resorts. Orderly brigades of Suffragette Scouts operated much like the Clarion Scouts to take the suffrage message to outlying areas.

Parades, processions and pilgrimages also featured suffrage cyclists. Rosa May Billinghurst, a suffragette from Lewisham who used an adapted tricycle as a wheelchair, was often seen on WSPU parades through London. Cyclists accompanied the 1913 NUWSS Pilgrimage, which saw suffragists follow eight routes across England to converge on Hyde Park for a mass meeting. The cyclists’ role was to ride ahead to scout for accommodation, announce meetings and distribute pamphlets. Suffrage caravan tours used cycling outriders in a similar fashion. Letters held at the Women’s Library, LSE reveal that when Ray Strachey (née Costello) volunteered for the NUWSS van tour from Scotland to Oxford, she took her bicycle with her.

Cycling played a more insidious role during the WSPU’s militant phase. Suffragettes on  arson and vandalism missions found bicycles convenient for transportation and other creative purposes. According to The Glasgow Herald, for example, in 1914 two militant set out by bicycle in a failed attempt to blow up Burns Cottage in Alloway, the birthplace of the poet Robert Burns. Cyclists were accused of a number of “Pillar Box Outrages,” riding up to post boxes and damaging the royal mail with oil or corrosive substances. Golf courses were a favourite target for cycling suffragettes, either to tear up the green with their tyres or heckle politicians at play.

arson and vandalism missions found bicycles convenient for transportation and other creative purposes. According to The Glasgow Herald, for example, in 1914 two militant set out by bicycle in a failed attempt to blow up Burns Cottage in Alloway, the birthplace of the poet Robert Burns. Cyclists were accused of a number of “Pillar Box Outrages,” riding up to post boxes and damaging the royal mail with oil or corrosive substances. Golf courses were a favourite target for cycling suffragettes, either to tear up the green with their tyres or heckle politicians at play.

Beyond of their political work, suffragists and suffragettes also cycled for pleasure and transport—we can’t forget that these women found riding just as practical and as much fun as we do today. The Women’s Suffrage Who’s Who, a 1913 directory to the suffrage movement including bios of nearly 800 women, lists cycling as their fifth most popular outdoor recreation. Sylvia, for her leisure activities, reported “I haven’t time for any.”

Cycling Activism WWI to Today

The outbreak of war in 1914 brought great change to both the suffrage movement and bicycle culture. The WSPU under Emmeline and Christabel ceased to campaign for women’s suffrage and channelled its efforts into the war effort.

The outbreak of war in 1914 brought great change to both the suffrage movement and bicycle culture. The WSPU under Emmeline and Christabel ceased to campaign for women’s suffrage and channelled its efforts into the war effort.

Sylvia and others disagreed with this approach, continuing their work for women’s enfranchisement through the East London Federation of Suffragettes. As women were recruited into war work, they jumped on their bicycles, normalising women’s cycling for transportation.

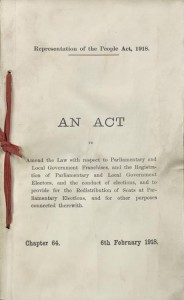

The 1918 The Representation of The People Act enfranchised women over the age of 30 who met the property qualification. This was a small victory on the road to full emancipation. For Sylvia, there was much more work to be done. She continued to campaign on for equality behalf of women workers and labourers of sexes. Finally in 1928, women received the vote on equal terms to men.

If we time leap forward in time to today, women’s cycling is undergoing a renaissance. More and more women are taking to their bikes for recreation, transportation and politics. Cycling has never been more alive as part of activism, such as the Pedal4Progress riders who helped raise funds and awareness in support of the Sylvia Pankhurst memorial sculpture soon to be erected in Clerkenwell Green.

From the Clarionettes to Suffragettes, Sylvia and her fellow political campaigners harnessed the power of the bicycle as an ally in the fight for equality. I hope the story of Sylvia Pankhurst and her cycling sisters inspires you to get on your bike too.

**For a PDF version of the lecture, click here.

Selected Sources and Recommended Reading

Archives and Special Collections

British Library, St. Pancras and Colindale, London

National Cycle Archives, Modern Records Centre, Warwick

The Women’s Library, London

Newspapers and Periodicals

Daily Herald

Jus Suffragii

Lady Cyclist

The New York Times

The Pall Mall Gazette

The Times (London)

The Suffragette

The Vote

The Women’s Suffrage Who’s Who

Votes for Women

Wheelwoman

Women’s Franchise

Secondary Sources

Atkinson, Diane. The Purple, White and Green: Suffragettes in London 1906-1914. London: Museum of London, 1992.

Crawford, Elizabeth. Women’s Suffrage Movement a Reference Guide, 1866-1928. London: UCL Press, 1999.

Hanlon, Sheila. “Cycling to Suffrage: Bicycles and the Organised Women’s Suffrage Movement in Britain, 1900-1914,” Cycle History, (Spring 2013)

Harrison, Shirley, Sylvia Pankhurst: The Rebellious Suffragette. London: Sapere Books, 2012.

Herlihy, David. Bicycle: The History. London & New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004.

Kay, Joyce “No Time for Recreations till the Vote is Won? Suffrage Activists and Leisure in Edwardian Britain,” Women’s History Review, 16, no 4, (September 2007) 535-553.

Liddington, Jill and Jill Norris. One Hand Tied Behind Us: The Rise of the Women’s Suffrage Movement. London: Virago, 1978.

Macey, Sue. Wheels of Change: How Women Rode the Bicycle to Freedom National Geographic Society, 2011.

McCrone, Kathleen. Sport and the Physical Emancipation of English Women, 1870-1914. London: Routledge, 1988.

Pankhurst, E. Sylvia. The Suffragette Movement. London, New York, Toronto: Longmans Green and Co, 1931.

Pankhurst, Richard. Sylvia Pankhurst, Artist and Crusader. London: Paddington Press, 1979.

Pye, Denis. Fellowship in Life: The National Clarion Cycling Club, 1895-1995. Bolton: Clarion Publishing, 1995.

Simpson, Clare S. “Respectable Identities: New Zealand Nineteenth Century ‘New Women’- on Bicycles!,” International Journal of the History of Sport 18, no. 1 (2001): 54-77.

Ticker, Lisa. The Spectacle of Women: Imagery of the Suffrage Campaign 1907-1914. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988.

Whitmore, Richard. Alice Hawkins and the Suffragette Movement in Edwardian Leicester. Derby: Breedon Books Publishing Co Ltd, 2007.

Picture Credits

Maquette of Ian Walters’ statue of Sylvia Pankhurst to be raised on Clerkenwell Green http://sylviapankhurst.gn.apc.org/

Portrait of Sylvia Pankhurst c 1890s, Postcard, The Women’s Library at LSE

Angel of Freedom WSPU logo designed by Sylvia Pankhurst, c 1906-8, Museum of London

Sylvia at the East London Federation of Suffragettes HQ, Bow Road 1912, Sylvia Pankhurst Trust

The Clarion Cycling Club Clarion meet Bakewell, Whitsuntide 1914, Ripley and District Heritage Trust

Book Cover, Denis Pye, Fellowship is Life, 2004

Rudge Whitworth Bicycle Poster, c 1900, Rennert’s Gallery

“Jessie and Gertrude,” Punch, 1895

Ipswich Votes for Women Shop with Bicycle c 1909, “Ipswich Icons: Looking at the Suffragettes and their links to the buildings of Ipswich,” Ipswich Star, 7 April 2015

Suffragettes Promoting a talk by Mrs Pankhurst 1914, “How the bicycle became a symbol of women’s emancipation,” Guardian, 4 November 2011.

“Suffragettes versus Churchill,” Newspaper clipping, Collection of Sheila Hanlon

Representation of the People Act 1918, Parliament UK Archive