Early one morning at the end of August 1884, Elizabeth Robins Pennell and her husband Joseph Pennell strapped their luggage to their tricycle and wheeled out of Russell Square before anyone else was stirring. They headed south toward London Bridge, cutting through thick fog and passing a policeman carefully testing every door on his last rounds as they made their way through the quiet streets.

Just beyond Borough, they stopped briefly at the corner where the Tabard Inn had once stood, which was made famous by Chaucer five hundred years earlier as the assembly place for his nine and twenty pilgrims travelling to Thomas Becket’s shrine. This auspicious spot was the starting point of the Pennells’ own Canterbury tale, the first of many adventures a-wheel and the start of a series of popular travel books recounting their cycling excursions throughout England and Europe.

A decade later, another couple, Fanny Bullock Workman and William Hunter Workman made a name for themselves as travel writers documenting similar but more ambitious bicycle trips to remote destinations in Europe, the Sahara and India. Who were the pioneering women cyclists and writers that made up one half of each of these couples, what motivated them to embark on these journeys, and how did their experiences differ over the decade that divided them?

This post compares two early cycle-tourism excursions taken by these remarkable women and their husbands; the Pennell’s Canterbury pilgrimage and the Workman’s tour of Iberia, and considers how they reflect their perceptions and politics relating to the world at home and abroad, especially in the case of the status of women.

Victorian women travel writers Elizabeth Robins Pennell (shown left above) and Fanny Bullock Workman (shown right above) share many characteristics in common, though their lives did not overlap in any ways that brought the two together. Both were Anglo-Americans who grew up in North America as part of affluent families but spent much of their adult lives in Britain and Europe. Pennell and Workman were born 1855 and 1859 respectively, so were of a similar age, though Pennell’s travelogues date earlier than Workman’s. Both were deeply engaged with the intellectual culture of the day, Pennell through her work as a biographer and host of literary salons, and Workman through her scientific association with groups such as the Royal Geographers Society. They also similarly identified with early feminism and the women’s suffrage movement, and struggled throughout their lives to prove that they were equal to men. Their accomplishments as cyclists, writers, and intellectuals demonstrate how they worked towards equality in their own lives, and set an example for other women through their pioneering exploits as to what they could achieve by refusing to accept the gender conventions of the day.

The first of the two cycle-tourists to set out a-wheel was Elizabeth Robins Pennell. Born 21 February 1855 in Philadelphia, she was sent to a convent school at age 8 following the death of her mother. She remained at the school until age 17, though she ultimately rebelled against the life expected of a Catholic woman. Her Uncle Leland’s work as an author inspired her to take up writing. Her first book was a biography of feminist icon Mary Wollstonecraft published by William Godwin, Wollstonecraft’s widower, a subject choice indicative of her early commitment to women’s rights. It was through her involvement with periodicals that she met her husband to be Joseph, a Quaker who was also shaking free of family pressure to take up a respectable profession by going the route of artist. Elizabeth considered Joseph to be her intellectual equal from the start, and soon they were collaborating as writer and illustrator. By 1884, the pair was married and had landed a joint commission from The Century for a travel piece, a prospect which would inspire their first piece of cycling-literature.

The first of the two cycle-tourists to set out a-wheel was Elizabeth Robins Pennell. Born 21 February 1855 in Philadelphia, she was sent to a convent school at age 8 following the death of her mother. She remained at the school until age 17, though she ultimately rebelled against the life expected of a Catholic woman. Her Uncle Leland’s work as an author inspired her to take up writing. Her first book was a biography of feminist icon Mary Wollstonecraft published by William Godwin, Wollstonecraft’s widower, a subject choice indicative of her early commitment to women’s rights. It was through her involvement with periodicals that she met her husband to be Joseph, a Quaker who was also shaking free of family pressure to take up a respectable profession by going the route of artist. Elizabeth considered Joseph to be her intellectual equal from the start, and soon they were collaborating as writer and illustrator. By 1884, the pair was married and had landed a joint commission from The Century for a travel piece, a prospect which would inspire their first piece of cycling-literature.

Elizabeth Robins Pennell was among the first women to take up cycling when she learned to ride in the 1880s. In an article entitled “Cycling” for Lady Grevilles’ book Ladies in the Field: Sketches of Sport, a collection of essays on everything g from tiger hunting to punting published in 1894, Pennell wrote, “I remember my first experience in 1884, when I practiced on a Coventry ‘Rotary’ in the country round Philadelphia, and felt keenly that a woman on a cycle was still a novelty in the United States. I came to England that same summer, but the woman riders whom I met on my runs through London and the Southern Counties, I could count on the fingers of one hand.” She and Joseph invested in a Humber tandem tricycle in London, which they took on their early adventures. Later, when two wheel models became standard during the craze, they switched to individual bicycles.

Pennell knew her bicycles well. Pennell noted in her piece for Ladies in the Field that after years of improvements to tricycles to make them suited for women and better machines overall, “then came the greatest invention of all, the Woman’s Safety.” She even went so far as to consider the Sparrow women’s high wheeler of the 1880s, a machine similar to the American Star with the large wheel at the back and smaller pilot wheel out front, an arrangement she appreciated but critiqued noting “the awkwardness of mounting and dismounting made it impractical. In an article directed at youth called “Cycling” to St Nicholas magazine, she extolled the virtues of cycling compared to other sports, especially as a source of fresh air and escaping from the city to the countryside, declaring it the best form of transport for sightseeing. She recognized the double standard for boys and girls, suggesting that boys take up the penny farthing, adding “If I were a boy I would ride nothing else,” but then going on to say Safety bicycles were best for girls and women, and encouraging them to practice riding, mounting, and wear sturdy grey cloth costumes for practicality and modesty.

The Pennell’s first trip was diarized in A Canterbury Pilgrimage. The Pennells had originally intended to ride through Italy sketching Tuscan cities following Laurence Sterne’s route from his 1765 book as part of their commission for The Century magazine. When that trip was postponed due to the cholera outbreak that swept through Europe, they settled on the trail of Chaucer’s pilgrims as an alternative route on a literary theme. The final piece was dedicated to Robert Louis Stevenson, as “a record of one of our short journeys on a tricycle, in gratitude for the happy hours we have spent travelling with him on his Donkey.” The couple’s literary interests were a central organizing principle behind this and their other cycling travelogues. From the Tabard Inn where we last left the couple in the introduction to this article, they Pennells continued down the Old Kent Road then on to Deptford, West Greenwich, and over the bridge at Crayford. In Kent, the narrative turned from scenery to the condition of the people, noting poor women and children at work hop picking and an increase in tramps. The Pennells spent the first night in Rochester at the CTC headquarter in the Queen’s Head. On Day Two, they covered Rochester to Chatham and on to Sittingbourne, Rainham where they settled down at an inn, pleased with themselves for having ridden so well over the course of the afternoon.

The Pennell’s first trip was diarized in A Canterbury Pilgrimage. The Pennells had originally intended to ride through Italy sketching Tuscan cities following Laurence Sterne’s route from his 1765 book as part of their commission for The Century magazine. When that trip was postponed due to the cholera outbreak that swept through Europe, they settled on the trail of Chaucer’s pilgrims as an alternative route on a literary theme. The final piece was dedicated to Robert Louis Stevenson, as “a record of one of our short journeys on a tricycle, in gratitude for the happy hours we have spent travelling with him on his Donkey.” The couple’s literary interests were a central organizing principle behind this and their other cycling travelogues. From the Tabard Inn where we last left the couple in the introduction to this article, they Pennells continued down the Old Kent Road then on to Deptford, West Greenwich, and over the bridge at Crayford. In Kent, the narrative turned from scenery to the condition of the people, noting poor women and children at work hop picking and an increase in tramps. The Pennells spent the first night in Rochester at the CTC headquarter in the Queen’s Head. On Day Two, they covered Rochester to Chatham and on to Sittingbourne, Rainham where they settled down at an inn, pleased with themselves for having ridden so well over the course of the afternoon.

Just as the landlady laid the table and offered them a shandy-gaff, their peace was interrupted by a short balding man in a CTC uniform. Rushing through the door, he demanded “Are you the lady and gentleman that came in on the tandem?” Once they confirmed that they were indeed that couple, he went on at length about how he detested the machine, and described his own near death experience on one steered by his wife, not to mention the constant chaffing he endured from passer-byers on the road, adding “women are headless things, and easily frightened.” The sentiments shared by this balding CTC member were just the tip of the iceberg as far as negative attitudes towards women cyclists that the Pennells would encounter on later trips. Finally, leaving the bizarre encounter at the CTC headquarter behind them in Rainham, the pair reached their destination on Day Three: Thomas Becket’s shrine. “We stood in the holy place for which Monk and knight, Nun and Wife of Bath, had left husbands and nunnery, castle and monetary, and for which we braved the jests and jeers of London roughshod, and toiled over the hills and struggled through the sands of Kent.”

The Daily News called A Canterbury Pilgrimage “the most wonderful shilling’s worth modern literature has to offer.” The Pennells had hit upon a winning formula, one they would repeat in later books, with their combination of travel narrative, witty commentary, and evocative sketches of the landscapes they passed through. Once the cholera epidemic had abated, they climbed on their trusty tricycle and toured Italy, an eventful trip beginning in Florence and culminated in their arrest for scorching down the Corso in Rome, as recorded in An Italian Pilgrimage. They then sold the tricycle, paid the fine, and settled in Rome for four months. In 1888, the pair published Our Sentimental Journey through France and Italy, again making the trip by tricycle though the pair had by then also started to ride bicycles. To Gipsyland, published in 1893, traced the couple’s journey to Eastern Europe, this time on bicycles with Elizabeth riding the Marriot and Cooper “Ladies Safety” that she purchased in 1891.

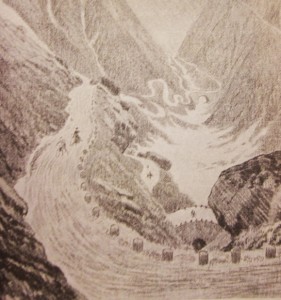

The Pennell’s final cycle-travelogue, Over the Alps on a Bicycle, published in 1898 for a popular audience, documented another adventure on two wheels and brought attention to Elizabeth’s record setting accomplishments as a lady cyclist. On this trip, the couple covered up to 108 miles per day, and crossed ten of the highest Alpine passes in six weeks. Edward Laroque Tinker commented in The Pennells, his 1951 biography of the couple that “This was no mean feat in those days when the female was not given to athletics and a woman on a wheel was looked upon askance. Elizabeth did not, however, originally set out with record breaking in mind, noting in her earlier contribution to Ladies in the Field noting that she was not a fan of record breaking by men or women and that while she may have broken records in the course of her rides she prized cycling for pleasure over racing, adding “the truth is, that, while every racing event is chronicled far and wide in the press, the tourist accomplishes her feats without advertisement, solely for the pleasure of travelling by bicycle.” By the time she embarked on her ride through the Alps, she had changed her opinion somewhat, noting “if the name of the first man to climb the Alps with his bicycle is disputed, I propose to immortalize the name and adventures of the first woman.”

The Pennell’s final cycle-travelogue, Over the Alps on a Bicycle, published in 1898 for a popular audience, documented another adventure on two wheels and brought attention to Elizabeth’s record setting accomplishments as a lady cyclist. On this trip, the couple covered up to 108 miles per day, and crossed ten of the highest Alpine passes in six weeks. Edward Laroque Tinker commented in The Pennells, his 1951 biography of the couple that “This was no mean feat in those days when the female was not given to athletics and a woman on a wheel was looked upon askance. Elizabeth did not, however, originally set out with record breaking in mind, noting in her earlier contribution to Ladies in the Field noting that she was not a fan of record breaking by men or women and that while she may have broken records in the course of her rides she prized cycling for pleasure over racing, adding “the truth is, that, while every racing event is chronicled far and wide in the press, the tourist accomplishes her feats without advertisement, solely for the pleasure of travelling by bicycle.” By the time she embarked on her ride through the Alps, she had changed her opinion somewhat, noting “if the name of the first man to climb the Alps with his bicycle is disputed, I propose to immortalize the name and adventures of the first woman.”

One feature of the Pennells’ narrative that stands out is their social commentary about the people and living conditions they encountered along their travels. This first becomes apparent in the description of poor women and children hop picking and the presence of much maligned tramps in Kent. In rural Italy, they wrote about the quaintness of peasant life, passing “wagon after wagon, piled with boxes and baskets, poultry and vegetables, and sleeping men and women,” priests in black robes, women doing their laundry in the stream, little girls in kerchiefs plaiting straw, a lady swineherd, and families picking chestnuts in shady groves. The status of local women and their reactions to a fellow woman on a bicycle was something Elizabeth paid particular attention to. Her descriptions of women are reminiscent of the makings of maternal feminism. Just outside Florence, a nun covered her face when the cyclist neared her on the road as though she “though is a device of the devil,” whereas a female innkeeper in Empoli who had never seen a tricycle asked an abundance of questions. In Foligno, people refused to make way for the tricycle, and “one woman in her stupidity or obstinacy walked directly in front of the machine, and when the little wheel caught in her dress, though no fault of ours, cried ‘Accident evoi!’” and seemed to wish an accident on them. In Albergo Marzocca, the reception to cyclists was better, though “as friendly as these people were, they were stupid.”

One feature of the Pennells’ narrative that stands out is their social commentary about the people and living conditions they encountered along their travels. This first becomes apparent in the description of poor women and children hop picking and the presence of much maligned tramps in Kent. In rural Italy, they wrote about the quaintness of peasant life, passing “wagon after wagon, piled with boxes and baskets, poultry and vegetables, and sleeping men and women,” priests in black robes, women doing their laundry in the stream, little girls in kerchiefs plaiting straw, a lady swineherd, and families picking chestnuts in shady groves. The status of local women and their reactions to a fellow woman on a bicycle was something Elizabeth paid particular attention to. Her descriptions of women are reminiscent of the makings of maternal feminism. Just outside Florence, a nun covered her face when the cyclist neared her on the road as though she “though is a device of the devil,” whereas a female innkeeper in Empoli who had never seen a tricycle asked an abundance of questions. In Foligno, people refused to make way for the tricycle, and “one woman in her stupidity or obstinacy walked directly in front of the machine, and when the little wheel caught in her dress, though no fault of ours, cried ‘Accident evoi!’” and seemed to wish an accident on them. In Albergo Marzocca, the reception to cyclists was better, though “as friendly as these people were, they were stupid.”

A lack of lady cyclists on the continent is often cited by the Pennells as evidence that they are travelling in underdeveloped countries compared to Britain or the US, especially in regards to the status of women and condition of the family. The contrast between women at home and abroad was also a subtle reminder that Elizabeth herself was doing something daring and liberated. While waiting for a boat to take them around an Alpine lake, the Pennells met two American women on a bicycle tour, the only lady cyclists they would encounter on the entire trip until the last leg back to Calais where they were joined by a German “frau” in knickerbockers on her way to Lake Como carrying a pistol and sketchbook who Elizabeth assessed as not a serious cyclist. The Pennells consistently position themselves as superior to the people they encounter, noting their naivety, unenlightened life styles, and insults directed at cyclists as evidence of cultural inferiority, often in a tone that is less than flattering of their own Anglo-American privilege.

The second of our cyclists, Fanny Bullock Workman, four years’ Elizabeth Robins Pennell’s junior, was born to a wealthy Worcester Massachusetts family in 1859. Her father was a successful business man and Republican Massachusetts governor, which meant Fanny was afforded the best education money could buy, including finishing school in New York. In his 2012 book Game Faces: Five Early American Champions and the Sports they Changed, Thomas Pauly suggested her thirst for adventure was evident early in life, and that she “chafed at the constraints of her privilege.” She took up travel after graduating, living in Paris and Dresden and writing adventure stories about debutante girls running away to Europe with handsome young suitors, undoubtedly something she fantasized about doing herself.

The second of our cyclists, Fanny Bullock Workman, four years’ Elizabeth Robins Pennell’s junior, was born to a wealthy Worcester Massachusetts family in 1859. Her father was a successful business man and Republican Massachusetts governor, which meant Fanny was afforded the best education money could buy, including finishing school in New York. In his 2012 book Game Faces: Five Early American Champions and the Sports they Changed, Thomas Pauly suggested her thirst for adventure was evident early in life, and that she “chafed at the constraints of her privilege.” She took up travel after graduating, living in Paris and Dresden and writing adventure stories about debutante girls running away to Europe with handsome young suitors, undoubtedly something she fantasized about doing herself.

In 1879, she returned to the US, where she met William Workman, a physician 12 years her senior who she married in 1881. William introduced Fanny to mountain climbing, which she excelled at. American alpine clubs in this era welcomed female members and the pastime fit with the new woman image that Fanny identified with. In 1889, the couple relocated to Europe due to William’s poor health, a move Fanny certainly would have endorsed. Substantial inheritances from both of their families meant that they could afford to travel and pursue alpine climbing, often with an entourage assisting them. Their daughter Rachel, born in 1883 was soon big sister to Siegfried, born in 1889. Fanny never embraced motherhood and felt it cramped her style as a writer and adventurer. Pauly noted that after having children Fanny “aggressively pursued alternative identity, one that liberated her from the conventional responsibilities of wife and mother.” She embraced the bicycle as a way to achieve this.

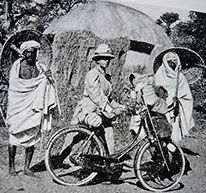

While the Pennell’s work was literary in its tone, richly descriptive, and illustrated with Joseph’s sketches, the Workmans’ fashioned themselves as serious contributors to scientific knowledge and used photographs to document their trips. The content of their books advanced from adventure journalism with personal anecdotes in early books to more rational scientific and cartographic studies in later works. The pair tended to write their sections separately, which they dedicated to each other. The resulting cycle-travelogues are dense with historic, scientific, and anthropological detail, such as the history and architecture of the Alhambra, analysis of glaciation in the Himalayas or vivid descriptions of the costumes worn by villagers on the Indian Plain. This writing style fits into the popular travel writing style of the day with its mix of adventure, travel narrative, and personal diarizing with an additional emphasis on cultural and scientific observations. Fanny in particular strove to have her research and writing recognized by the Royal Geographic Club and other Alpine societies, so she consciously adopted a rational and informative in voice. After years of resistance, she eventually became the second woman, after Elizabeth Bird, to address the Royal Geographical Society and the first to lecture at the Sorbonne. Fanny was highly competitive, not just men but also with her female contemporaries. When Annie Peck claimed a new altitude record in 1908 by ascending Peru’s Nevado Huarascan, therefore bettering Workman’s 1906 record set at Pinnacle Peak in the Himalayas, Fanny challenged the claim and hired a survey team at her own expense to prove Peck’s climb was less than her own, thereby retaining the record.

While the Pennell’s work was literary in its tone, richly descriptive, and illustrated with Joseph’s sketches, the Workmans’ fashioned themselves as serious contributors to scientific knowledge and used photographs to document their trips. The content of their books advanced from adventure journalism with personal anecdotes in early books to more rational scientific and cartographic studies in later works. The pair tended to write their sections separately, which they dedicated to each other. The resulting cycle-travelogues are dense with historic, scientific, and anthropological detail, such as the history and architecture of the Alhambra, analysis of glaciation in the Himalayas or vivid descriptions of the costumes worn by villagers on the Indian Plain. This writing style fits into the popular travel writing style of the day with its mix of adventure, travel narrative, and personal diarizing with an additional emphasis on cultural and scientific observations. Fanny in particular strove to have her research and writing recognized by the Royal Geographic Club and other Alpine societies, so she consciously adopted a rational and informative in voice. After years of resistance, she eventually became the second woman, after Elizabeth Bird, to address the Royal Geographical Society and the first to lecture at the Sorbonne. Fanny was highly competitive, not just men but also with her female contemporaries. When Annie Peck claimed a new altitude record in 1908 by ascending Peru’s Nevado Huarascan, therefore bettering Workman’s 1906 record set at Pinnacle Peak in the Himalayas, Fanny challenged the claim and hired a survey team at her own expense to prove Peck’s climb was less than her own, thereby retaining the record.

As cycle-tourists, Fanny and William started big. Their first cycling trip, the subject of Sketches A Wheel in Modern Iberia published in 1897, was a 2,800 mile trek across Spain in 1895, a contrast with the smaller jaunt from London to Canterbury that the Pennells started out with. The same year, they travelled through North Africa as documented in Algerian Memories. Also different was their choice of machine—while the Pennell’s beginner bike was a tandem tricycle, the Workmans set out on steel frames, rubber tyred Safety bicycles, each carrying 20 pounds of luggage. One of the bicycles proved unsound, and had to be traded half way through the trip, and both were prone to punctures on the rough roads of Spain. The pair averaged 45 miles per day overall and up to 80 miles on some days. Alpine climbing and mountaineering were mixed into the trip, with the couple often leaving their bicycles behind to walk up peaks, such as those clustered with monasteries above Monserrat. Their account of the journey describes their everyday experiences, while filling in detail about the history of the places they visit, the nature of people encountered, and the geography of the landscapes they traveled through. Not all their experiences were positive. One day, a muleteer angry that the Workman’s bicycles had spooked his animals, tried to bar their way and threatened them with a mattock with a heavy handle and an iron blade. “When he came within about ten feet,” Fanny wrote, “seeing that something more than words was necessary, we drew our revolvers and covered him. He retreated, and the cyclists carried on down the road, revolvers in hand.

As cycle-tourists, Fanny and William started big. Their first cycling trip, the subject of Sketches A Wheel in Modern Iberia published in 1897, was a 2,800 mile trek across Spain in 1895, a contrast with the smaller jaunt from London to Canterbury that the Pennells started out with. The same year, they travelled through North Africa as documented in Algerian Memories. Also different was their choice of machine—while the Pennell’s beginner bike was a tandem tricycle, the Workmans set out on steel frames, rubber tyred Safety bicycles, each carrying 20 pounds of luggage. One of the bicycles proved unsound, and had to be traded half way through the trip, and both were prone to punctures on the rough roads of Spain. The pair averaged 45 miles per day overall and up to 80 miles on some days. Alpine climbing and mountaineering were mixed into the trip, with the couple often leaving their bicycles behind to walk up peaks, such as those clustered with monasteries above Monserrat. Their account of the journey describes their everyday experiences, while filling in detail about the history of the places they visit, the nature of people encountered, and the geography of the landscapes they traveled through. Not all their experiences were positive. One day, a muleteer angry that the Workman’s bicycles had spooked his animals, tried to bar their way and threatened them with a mattock with a heavy handle and an iron blade. “When he came within about ten feet,” Fanny wrote, “seeing that something more than words was necessary, we drew our revolvers and covered him. He retreated, and the cyclists carried on down the road, revolvers in hand.

The Workmans’ encounters with people reveal a great deal about what it was like to be Anglo-American tourists from a privileges background travelling in foreign lands and how the Workman perceived themselves and others. The local people described in Sketches A Wheel tended to be rural peasants observed at a distance and described in naive terms, village inhabitants interacted with only fleetingly and often with an element of cultural misunderstanding on both party’s accounts, and those serving them at hotels. Observations about women are particularly interesting. One inn mistresses is described rather crudely as an oily Spanish women. The Workmans were shocked when Fanny was barred entry to Corpus Christi chapel, Valencia to see the baroque painter Francisco Ribalta’s altarpiece because her head wasn’t covered by the traditional black mantilla that most women wore, a sure sign of the low status of women in late-Victorian eyes. In stark contrast with Fanny’s own fearlessness as an explorer, Spanish women come across as terrified of anything new, but possessed of a child like curiosity. At one point in the mountains, women doing laundry scurry away and hide when they see Fanny and her machine. Near the end of their trip on a downhill slope leading to Zaragoza, a town where the people, “notably the women, stared like cattle” Fanny noted “a woman with four frightened children clinging to her skirts stood outside and watched our approach.” They bluntly remark on the “backwardness” of the people of Aragon. If the Workman’s estimation, the Spanish come across as a semi-exotic people lacking refinement, with the men occasionally brutish, women timid, and all lacking intelligence.

The Workmans’ subsequent cycling trips are recorded in Algerian Memories: A Bicycle Tour over the Atlas to the Sahara in 1895 and Through Town and Jungle: Fourteen Thousand Miles A-Wheel Among the Temples and People of the Indian Plain (1904). Though they made a significant contribution to cycling-journalism, climbing remained Fanny’s preferred pastime and after 1898 she shifted her focus back to alpine exploration, making a remarkable eight excursions into the Himalayas over the next few years and writing about them in books such as In the Ice World of the Himalayas in 1900 and Two Summers in the Ice-Wilds of Eastern Karakoram: The Exploration of Nineteen Hundred Square Miles of Mountain and Glacier in 1916. Her later books were to have an even greater focus on scientific detail as she continued to seek recognition from alpine societies, as well as anthropological observations, many deeply orientalist, as she met and recorded the lives of people living on the very edge of empire.

Elizabeth Robins Pennell and Fanny Bullock Workman both identified with the strains of feminism characteristic of their era, but expressed their political ideals in very different ways in their writing and public personas. One thing they shared in common was their attitude to dress, a critical issue in the gender politics at the time. Though rational dress was beginning to catch on for outdoor sports in the 1890s-1910s and Workman and Pennell recognised it as a superior garment for cycling and climbing, they both chose to wear skirts rather than knickerbockers, thereby retaining an appearance associated with respectable femininity. Pennell’s work dates to the pre-organized suffrage era, when cause-specific feminist groups were strong but the campaign for the vote had not yet materialized as the dominant movement. Her writing is not overtly feminist, despite the fact she clearly challenged prevailing gender conventions through her cycling adventures. This is a stark contrast with contemporary works such as Frances Willard’s Wheel within A Wheel: How I Learned to Ride A Bicycle which positions mastering a bicycle as a step towards women’s equality, or Maria Ward’s Bicycling for Ladies which actively encouraged women to seek independence through cycling. Pennell’s work champions her accomplishments as a woman, an individual, and a wife and presents a highly readable and personal account of her travels in a style that would have appealed to a wide audience. While her feminist instincts may have inspired her pursuits, a heavy feminist polemic would not have served her purposes as a popular author and pleasure cyclist.

Workman’s dedication to feminism and the suffrage campaign, however, is readily apparent in her work, a reflection of the prominence women’s rights had risen to over the decade that divided her writing from Pennell’s. Throughout her life, Workman battled for recognition by the male-dominated climbing and scientific communities. The fact that American alpine clubs encouraged women to join, unlike their European counterparts, meant that Fanny would have been exposed to other liberated women on the mountainside in her youth. Later when the women’s suffrage movement gained momentum, she aligned herself with the WSPU. In 1912, she was photographed atop a 21,000 foot plateau in Karakoram holding an issue of “Votes For Women” magazine, a photograph she later used as one of her book covers, a bold political statement leaving no doubt about her belief in women’s rights. In her cycle-travelogues, Workman frequently commented on the oppression and deplorable treatment of women she encountered abroad, such as in the powerless group of women she met in the harem she visited in Algerian Memories. A commitment to women’s rights was part of the public identity that Workman cultivated and feminist aspirations were linked to her achievements and aspirations as a cyclist, climber, and amateur scientist.

Workman’s dedication to feminism and the suffrage campaign, however, is readily apparent in her work, a reflection of the prominence women’s rights had risen to over the decade that divided her writing from Pennell’s. Throughout her life, Workman battled for recognition by the male-dominated climbing and scientific communities. The fact that American alpine clubs encouraged women to join, unlike their European counterparts, meant that Fanny would have been exposed to other liberated women on the mountainside in her youth. Later when the women’s suffrage movement gained momentum, she aligned herself with the WSPU. In 1912, she was photographed atop a 21,000 foot plateau in Karakoram holding an issue of “Votes For Women” magazine, a photograph she later used as one of her book covers, a bold political statement leaving no doubt about her belief in women’s rights. In her cycle-travelogues, Workman frequently commented on the oppression and deplorable treatment of women she encountered abroad, such as in the powerless group of women she met in the harem she visited in Algerian Memories. A commitment to women’s rights was part of the public identity that Workman cultivated and feminist aspirations were linked to her achievements and aspirations as a cyclist, climber, and amateur scientist.

The Pennells and Workmans’ style of cycle-travel writing fit into the genre of travel writing popularised in the late-nineteenth century West. Other cycle travel publications dating to the time included Frank Lenz’s Around the World with Bike and Camera (1892) published before the cyclist mysteriously vanished abroad and Thomas Steven’s Around the World by Bicycle Vol 1&2 (1887) about his journey by penny farthing. All presented riveting road stories that mixed personal anecdotes, descriptions of landscape, informative details about the significance of the places visited, and descriptions of people in far off lands together into highly readable books that would have been popular with armchair adventure seekers back home. What Elizabeth Robins Pennell and Fanny Bullock Workman add to the genre is an element of feminist critique, though often subtle, which speaks volumes about the changing place of daring women in modern Britain and their perspectives on the status of women in places that did not share the advancements in progress that they had benefitted from back home. In the decade that divided the Pennell and Workman’s first cycle trips, taken in 1884 and 1895 respectively, women’s rights developed into a mainstream discussion, a factor which is reflected over their writing careers such that Pennell observes inequality while avoiding a distinct feminist polemic whereas Workman openly aligned herself with the women’s rights and the women’s suffrage movement.

While this post has considered a selection of the Pennell and Workman’s early cycling travelogues from trips in England and Continental Europe, there is much scope to look at how their political commentary developed in later books, especially as they ventured further abroad to Eastern Europe, Africa and India. The observations of these self-made and self propelled Anglo-American envoys into distant lands reveal much about gender, imperial, colonial, and global politics in a changing world and provide a snapshot of places and people that would become inaccessible to tourists a few years later with the outbreak of war.

Selected Sources

Pauly, Thomas. Game Faces: Five Early American Champions and the Sports they Changed. (2012)

Pennell, Elizabeth Robins. “Cycling,” St Nicholas. (July 1890)

Pennell, Elizabeth Robins. “Cycling” in Lady Greville, Ladies in the Field: Sketches of Sport. (1894)

Pennell, Elizabeth Robins and Joseph. A Canterbury Pilgrimage. (1884)

Pennell, Elizabeth Robins and Joseph. An Italian Pilgrimage (1887)

Pennell, Elizabeth Robins and Joseph. Our Sentimental Journey through France and Italy. (1888)

Pennell, Elizabeth Robins and Joseph. To Gispyland. (1893)

Pennell, Elizabeth Robins and Joseph. Over the Alps on a Bicycle. (1898)

Tinling, Marion. Women into the Unknown: A Sourcebook on Women Explorers and Travelers. (1989)

Tinker, Edward Laroque. The Pennells. (1951)

Workman, William and Fanny Bullock. Algerian Memories: A Bicycle Tour over the Atlas to the Sahara. London: Fisher Unwin. (1895)

Workman, William and Fanny Bullock. Sketches A Wheel in Modern Iberia. (1897)

Workman, William and Fanny Bullock. Through Town and Jungle: Fourteen Thousand Miles A-Wheel Among the Temples and People of the Indian Plain. (1904)

Workman, Fanny Bullock. In the Ice World of the Himalayas. (190