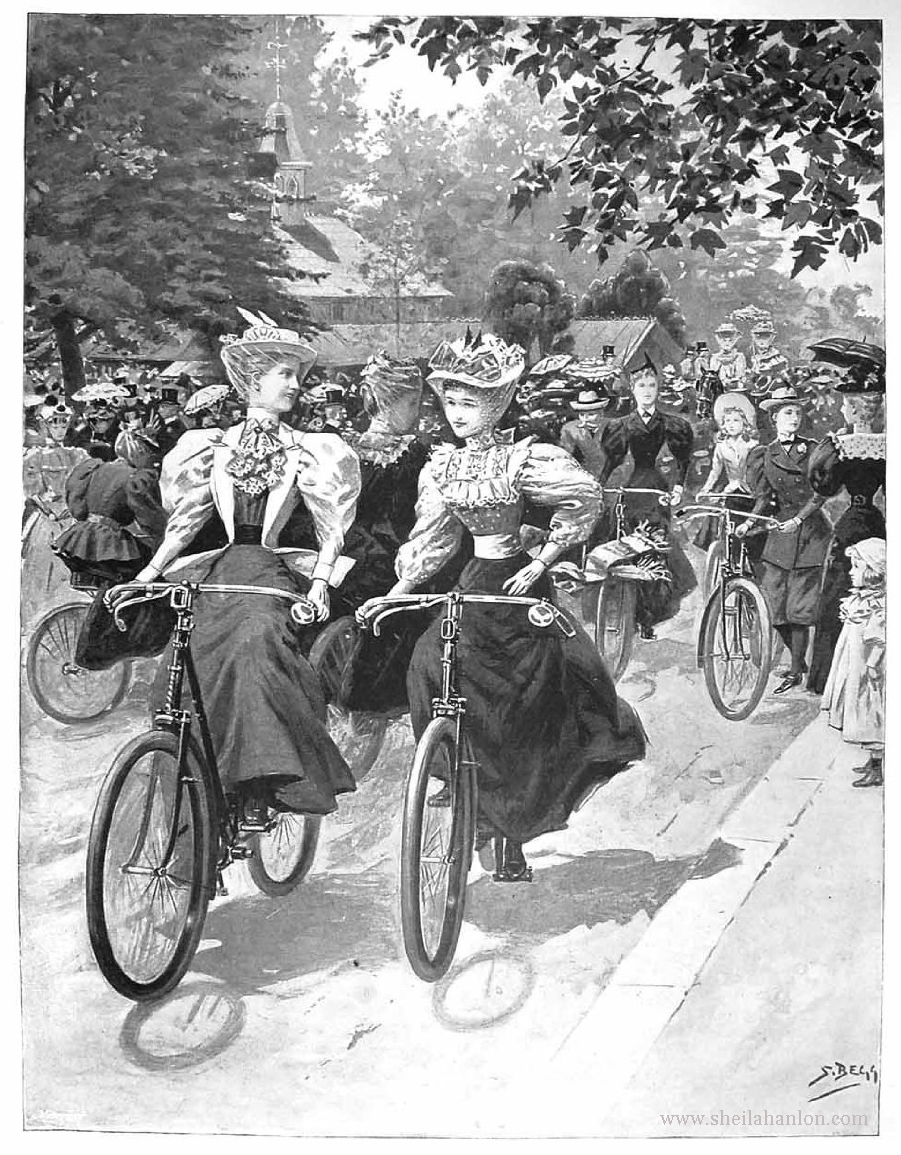

The bicycle literally and figuratively transported women beyond the bounds of the home and into public space in late-Victorian London. Not surprisingly, this incursion into open areas, such as city streets and country lanes, caused mild moral panic among a society clinging to increasingly outmoded ideas about the division of space into masculine and feminine spheres. Parks emerged as an in-between space where women’s cycling was accepted as part of a leisure trend popular with the respectable classes, which by Victorian definitions meant middle and upper class riders. Battersea Park in particular became known as the park of the lady cyclist during the craze years. Illustrations such as Samuel Begg’s interpretation of the Battersea Park cyclists’ row shown above depict a robust cycling culture as early as 1895 populated in the majority by women taking their leisure a wheel.

Battersea’s development as a cycle park was in part due to an accident of legislation. When the craze began around 1895, bicycles were banned in open spaces falling under the Parks Regulation Act, which had jurisdiction over royal and municipal parks, including Hyde Park, Regent’s Park, and St. James’s Park. With these central greens off limits, there was a distinct want of a suitable grounds for cycling within city bounds. Battersea Park, however, was exempt from the Parks Regulation Act so lady cyclists soon gravitated there. The park, located south of the Thames in Surrey, was a relatively new park which had been established as part of a government intervention scheme to regenerate what had once been a notorious and impoverished part of town where raucous fairs were held.

Based on Thomas Cubitt’s 1843 recommendations to Queen Victoria’s Commission for Improving the Metropolis, an act was passed in 1846 allowing for the formation of a Royal Park in Battersea Fields. Three hundred and twenty acres were annexed, nearly two hundred of which were enclosed as parkland. In the 1890s, local Labour MP John Burns petitioned to have the park locally administrated, rather than put under royal parks jurisdiction. Burns’s vision was to maintain the park as an open green space for the use and benefit of the working class people who lived in the vicinity as a healthy alternative to other less desirable recreations such as drink and the music hall. For the duration of the cycle craze, the park was managed by the LCC, which proved amenable to cyclists.

Though not intended explicitly for them, the middle classes who were drawn en masse to cycling in the 1890s benefited from Burns’ improving park plan. In the summer of 1895, The Pall Mall Gazette observed, “it seemed as if the whole of the aristocratic wheeling population pounced upon the spot at one and the same time.” The park’s primary appeal was unrestricted cycling access at a time when bicycles were banned in other parks. Its physical attributes were also a draw. Smooth, hard-surfaced paths shaded by mature trees traced the park’s perimeter, ran along the river, and cut through design features, including a tropical garden. Since the property had been leveled, the route was flat and effortless to ride. The riverside path was nearly two miles long, and the route running inland was one and a quarter miles in length. A full circuit of the park covered six-and-a-half miles, which was considered an ideal length for a woman’s run.

Though not intended explicitly for them, the middle classes who were drawn en masse to cycling in the 1890s benefited from Burns’ improving park plan. In the summer of 1895, The Pall Mall Gazette observed, “it seemed as if the whole of the aristocratic wheeling population pounced upon the spot at one and the same time.” The park’s primary appeal was unrestricted cycling access at a time when bicycles were banned in other parks. Its physical attributes were also a draw. Smooth, hard-surfaced paths shaded by mature trees traced the park’s perimeter, ran along the river, and cut through design features, including a tropical garden. Since the property had been leveled, the route was flat and effortless to ride. The riverside path was nearly two miles long, and the route running inland was one and a quarter miles in length. A full circuit of the park covered six-and-a-half miles, which was considered an ideal length for a woman’s run.

By 1895, Battersea’s cycle parade was one of the highlights of the season. The unprecedented crowds of thousands of lady cyclists who congregated in the park during the cycling craze attracted much attention. The Times noted in 1895 that, “This year has witnessed a great development of cycling among ladies, and the parks, especially Battersea, have become quite a parade-ground for them.” The scene left a powerful impression on Jerome K. Jerome, who recalled in My Life and Times, that,

“In Battersea Park, any morning between eleven and one, all the best blood in England could be seen, solemnly peddling up and down the half-mile drive that runs between the river and the refreshment kiosk… In shady bypaths, elderly countesses, perspiring peers, still at the wobbly stage, battled bravely with the laws of equilibrium; occasionally defeated…daughters of a hundred Earls might be recognized by the initiated, seated on the gravel, smiling feebly and rubbing their heads.”

Images of Battersea Park from this era, such as Samuel Begg’s image at the top of this post, depict its paths teeming with neat rows of impeccably dressed lady cyclists. The Queen’s London printed the image of the cyclists in Battersea Park shown right, and described the emergent cycling scene as,

“‘Better late than never,’ cyclists said when Society took to riding bicycles on every possible occasion. Someone discovered that the roads in Battersea Park were excellent. and ere long the cycling parade there became quite one of the sights of the 1895 season. Rotten Row, in Hyde Park, soon became almost deserted by riders on horse-back, who preferred wheeling at Battersea. Scores of ladies and gentlemen belonging to the upper classes could be counted on any fine morning cycling at Battersea…Our picture shows a few of the cyclists, one of whom, a lady, is evidently a novice.”

Though one of the riders does look a bit wobbly on her wheels, the image gives a strong impression of the throng of cyclists that could be observed most mornings in the park.

Battersea’s flourishing cycle promenade was supported by the parks’ infrastructure and amenities, as well as entrepreneurial schemes devised to capitalise on the cyclists’ row. Restaurants, cafes, and club enclosures provided a socially selective, comfortable, and safe place to meet friends and relax. The Lake House, a café attached to an LCC refreshment kiosk, was the park’s preeminent gathering spot. In an article called “The West End on Wheels,” for Badminton Magazine, August 1895 The Earl of Onslow described it as “a charming spot…where screened by a wealth of may and blossoming chestnut from the gaze of the passing cyclists, the breakfast table may be spread on the shores of the ornamental water.”

Cycling clubs often met for tea and riding in the park, including the exclusive Green Park Club and White’s Club. Novices could take lessons in the park, bicycles were available to rent, and porters offered to watch bicycles while their riders went for tea. Sections of grass were set aside as rest areas for the cyclists, and the park even had lavatory, much to the relief of many lady cyclists (pun intended). Riders could rest easy about crime and harassment, since constables patrolled the park in case of accident, crime, or cycling infractions–unless of course they were scorchers in which case the police were onto them.

Interestingly, the majority of the highly fashionable and well dressed women who rode in the park did not arrive there on their own pedal-powered volition. Instead, lady cyclists had their bicycles delivered by carriage and off-loaded by footmen. The carriages then waited, often in lines so thick that the LCC was forced to restrict standing vehicles in the park. Another option was to hire a machine on site, or arrange for an agent to bring a machine to the park as needed. Battersea Park’s proximity to a rail station made it convenient for women to transport their bicycles by train. For those who lived close to the park, and for whom chaperonage and public appearances were not an issue, it would have been simplest to arrive a-wheel. Once safely inside the park, anxieties about women’s cycling were alleviated by Battersea Park’s reputation as a respectable place for ladies to ride.

Society bicyclists were quick to desert Battersea Park when cycling hours were finally granted in Hyde Park late in the season in 1895. Nonetheless, Battersea had by then secured its reputation as an excellent cycle ground where women could ride relatively free from public comment or harassment faced on the roads. Spaces like Barrersea Park played an important role in gaining acceptance for women’s cycling as a popular leisure fad, a status that in turn helped to some extent minimise resistance to women’s cycling in the wider idea public sphere.

Selected Sources

Jerome K. Jerome, My Life and Times, 1926.

Badminton Magazine, August 1895, 124.

Pall Mall Gazette, August-November, 1895

Lady Cyclist, July 1895

Harper’s, January 1896

Golf and Cycling Illustrated, 1 April 1897, 18.

Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News, 1895

Queen, 16 March 1895

The Times, 1857, 1874, 1895

Wheelwoman, April 1897